Provincetown, 1957, 2011

/In the summer of 1957, when Patti Page had us all yearning for the quaint villages, sand dunes and salty air of Cape Cod, lucky Dick Bellamy was in Provincetown, enjoying what he later described as the best and “real-est” summer of his life. Dick was in his element in Provincetown, the place where, after leaving the Midwest nine years earlier, he found himself, literally and figuratively.

In 2011, when I learned that the Norman Mailer Writers Colony offered a week’s biography workshop in Provincetown, I applied and got in. We six participants were housed separately, and met every morning at Mailer’s spacious, bay-front home at the end of Commercial Street. It was largely as it had been at the time of the writer’s death four years earlier. We had a tour of his attic study, crammed with books, filing cabinets and dust bunnies. Our province was the living room, the deck, and the john that had been Mailer’s favorite—it seems he got so much thinking done there that he referred to it as his “second office.”

Mailer's "first" office

I wandered around Provincetown in my free time, trying to imagine what it must have been like when Dick first arrived more than sixty years before. Surely the wisteria was as lush, the birds as chattery, and the mosquitoes as pesky back then. I walked up and down Commercial Street to see if I could find places he favored. I kept an eye out for circular blue plaques that alerted visitors to Provincetown history. On one walk I discovered the writer Mary Heaton Vorse’s house. It was in her backyard that Dick met Sheindi Tokayer in 1957. Sheindi and her artist friend Jackie Ferrara were living in Heaton Vorse’s pony barn that summer. But when I walked down the driveway and around to the back, the pony barn was no longer there.

What I did see was a large patch of open ground that must have been where Sheindi and Jackie hosted outdoor pancake breakfasts on Sundays. On one of those days, Dick tagged along with a friend who introduced him to Sheindi, the woman who would share his life for the next seven years. A strange thing happened when I tried to return to the Heaton Vorse house for a return visit—I couldn’t find the place! It was as if, like Shangri-La, the fog had closed around it.

Pat de Groot

One afternoon I visited Dick’s friend Pat de Groot, a painter who still lives in the large, bayside house that she and her late husband Nanno de Groot designed and built in 1962 on a plot of land that cost them $6000. Over the years, Dick and his friends often gathered on her deck. The day I called on Pat, Baltimorean John Waters, her longtime summer tenant, was nowhere in sight.

Michael Shay’s, now closed

Another day I had lunch with Chris Busa, the founder and editor of Provincetown Arts. Chris took me to Michael Shay’s, and led me to the table where he and Norman Mailer would sit together to eat oysters. Chris told me that after eating each slippery morsel, Mailer would turn the shell over to see if he could detect a face in the happenstantial patterns of its crevices.

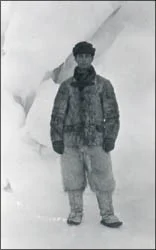

Donald Baxter MacMillan

One place I didn’t visit—I didn’t then know that Dick had a history with the place—was the childhood home of the arctic explorer Donald Baxter MacMillan. I would later learn that in 1957, Dick’s friend, painter Jim Bumgardner, was hired to paper a room in the historic house, and Dick volunteered to help him. Neither had experience with the tricky business of unfurling rolls, matching patterns and anchoring strips to the wall with glue. When their employer stopped by to check in on them, the two were dripping with glue and surrounded by mangled lengths of wallpaper. She was so amused that she called a halt to their work, and to their surprise, treated the skinny, would-be workers to dinner.

The late Deborah Martinson taught the biography workshop at the Mailer house. One of Deborah’s memorable assignments was to write a letter to the person we were writing about. By then, Dick had been dead for thirteen years. Here’s a portion of mine. “You were such an eccentric guy, dear Dick. When I started work on your biography, I tried to understand the odder things about you that your friends reported. Now I don’t care as much about explaining you. As if I could ever “explain” your quirky ways! Now I’m puzzling over a bigger mystery—how you came by your disinterest in profiting from the sale of art. It was the most subversive part of you. You handled some of the most lucrative talents of the sixties—you had the art world in the palm of your hand, and then you spread your fingers and it slipped away. You really can’t succeed in business without really trying, and you didn’t seem willing to try. But then, you never saw yourself as involved with commerce. Your Green Gallery was like an alternative space avant la lettre. There was no one, no one, like you. . .”